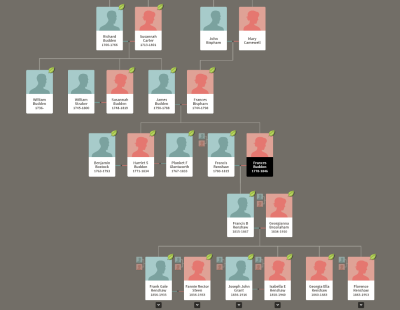

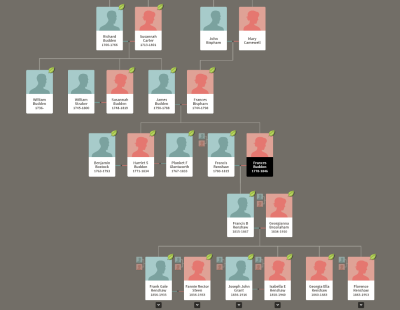

Yesterday I wrote about my great, great, great, great aunt Harriet Straker Budden and her husband, Benjamin Bostock. I mentioned that Harriet’s middle name came from her father’s (James Budden) business partner, William Straker, of Barbados, who was also her uncle by marriage to her aunt Susannah Budden. These people lived in 1700’s, so records aren’t that great, but church records can preserve christenings, marriages, and burials, and become a very good source of information. The census only recorded male heads of household up until about 1850, so those are of limited use until 1860. Still you can Google these names and see what turns up, and sometimes you will find a newspaper article (James Budden and William Straker would post about indentured servants they were hiring for their shop). It gets complicated by the lack of standardized spelling (a constant problem in the census as well) so William Straker’s last name was sometimes Stricker, Striker, or Streaker.

But one place I found William Straker’s name pop up several times was in a book recording the proceedings of the Pennsylvania government in 1778, not long after the American Revolution, while the United States was fighting against the British. The United States worked very hard to get France involved in the war and they finally had sent over a fleet of ships and 4,000 soldiers under the admiral Charles Hector, comte d’Estaing. d’Estaing also carried the new French ambassador Conrad Alexandre Gerard de Rayneval. His fleet was sufficiently powerful to blockade the British fleet in New York harbor. During this blockade, a British ship was captured and one of the passengers was William Straker. He was originally from Barbados, but had moved to Philadelphia previously. However in 1775 he went back to Barbados to sell his holdings, and while he was there the war broke out. Since Barbados was held by the British, he figured he could get a ship to Britsh-held New York and then once in New York, get around the battle lines and back to Philadelphia. However the French fleet intercepted the ship he was on, taking him prisoner, and now the new ambassador asked Pennsylvania to award him Straker’s five slaves he had with him. Straker was able to explain what happened and the Budden family vouched for him, so that eventually he was released and able to keep his slaves (these were his household staff and had been with him for years, so it was probably best for everyone for them to stay with Straker). All of this is told in a number of different entries in the proceedings of Pennsylvania’s government, starting with a letter from the ambassador and ending with Straker signing an allegiance to the United States and an order freeing him and returning his property to him. Now here are the French coming to the rescue of the United States and their ambassador (who was also instrumental in France’s decision to support the United States) has asked for something, so this was probably a pretty delicate issue.

Continue reading “William Straker”