For some reason I got the genealogy bug and I have been doing a lot of research the last couple of weeks. I want to get as much done as I can and then stop. It’s like putting together a puzzle, but I don’t want to make a career out of this puzzle.

I’ve been able to come up with a few different resources that have turned out to be pretty helpful and just want to list those.

One great resource is ancestry.com. A lot of people do genealogy and share their family trees there, plus they also have a ton of resources that are easy to look up. If you know a person’s name and the county they lived in, you should be able to find stuff out about them, which is pretty amazing considering a lot of the records are around 100 years old. You have to pay a monthly fee to use the best features of ancestry.com (some of it is free), but you can get a two-week trial which I am making good use of. And lately I am finding that familysearch.org’s Search feature (as opposed to its Find feature which is used to find people) is good for getting some of the same records as Ancestry has.

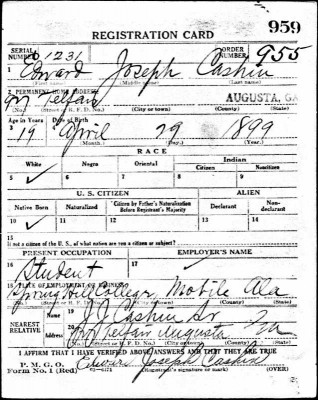

One resource that was helpful for a couple of people is World War I draft registration cards. All men between 18 and 40 were required to fill one of these out in 1918, and that includes both of my grandfathers, plus their brothers and cousins who are about that age. Papa filled his out when he was 19 years old and it says that he was attending Spring Hill College, which nobody in my immediate family knew, even the one who actually went to Spring Hill. We have a family connection to Spring Hill, but it didn’t happen until about 20 years after Papa filled out that card. The good thing about these cards is they give the full name and the birthday, which you don’t get from census records.

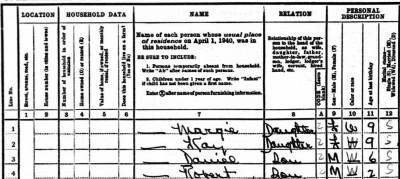

Another great thing at ancestry.com is being able to look up census records. The US Constitution requires a census be performed every 10 years, and we still account for every person in the United States every 10 years. The main reason this is done is to figure out how many Representatives each state gets, but obviously it gets other uses. Social Security numbers are still pretty recent, so at first they would go street by street and ask how many people lived at the house. On an old census (1840 and earlier) about all you got was the name of the head of household, the number of male and female children, the number of male and female adults, and the number of male and female child and adult slaves (slavery is bad, but the whole idea of a 10 year old slave takes it to another level). Later the census asked more questions and started identifying the individuals at the house. In 1850, everyone in the house was named. In 1880 they added the relation of each person to the head of household which really helps when there are in-laws and nephews involved. In 1860, our ancestor who came from Ireland, John, lived in the same household as another person from Ireland with the same last name, named Lawrence. Was he a brother, a cousin? We don’t know because Lawrence died before relations were listed. In 1870 it looks like Lawrence’s children are living with John, but we still don’t know the relation. By 1880, when relations are listed, the kids must have moved out. Later on, I read an article about John that Edward wrote in Fopab, and it turns out that John came to Augusta with two brothers: Lawrence and Patrick. I don’t see any census records of Patrick.

Some censuses asked people their job, income, value of their property, whether they could read, whether they had attended school, how old everyone is. While it never asked for birthdays, in 1900 they did ask the month and year of birth. They asked if you owned or rented your home, whether you worked for someone else or whether you owned your own business. They started asking how many years you had been married (so far everyone has agreed with their spouse). Not only does this pin down the number of children and their names (often spelled incorrectly, or nicknames, sometimes just initials), but you can guess the year of their birth. So if a kid is 12 in 1880, you can guess he was born in 1868 (though it could also be 1867 if he hasn’t had his birthday yet when they take the census). By putting together one census after another, you watch kids grow up, parents die, etc. You go and find the census for the grown kids and might see they have a parent living with them, or a brother or an in-law. Too often, a young child will just disappear, usually meaning they died young. Child mortality rates were horrible, but they seem to have made up for this by keeping women pregnant almost continuously. Eventually they did a better job of writing down the street and house number, and it is interesting to see a house change possession from one generation to the next. Sometimes families would live right next to each other and show up on the same census sheet. The census from about 1870 to 1920 is the best. There is a rule that a census has to be 72 years old before it is made public, so the 1940 census was just released last year. I noticed a gap where I had no census records for anyone in 1890. Wikipedia said about 25% of the records were burned that year and the rest were destroyed intentionally in a purge of government files. The fire led to the creation of the National Archives, which was formed to take better care of files.

The census doesn’t tell you everything, like exact birthdates, full names, maiden names, or when people die. A lot of times gravestones have that. There is a website called findagrave.com that has pictures of a lot of graves plus whatever information people can add. It is kind of like a wiki where people can add information and pictures, but you have to have an account to make changes. A lot of our ancestors, especially the ones at St. Michael’s cemetery in Pensacola, are indexed in Find a Grave. To show up in Find a Grave, it helps to be buried in a famous cemetery. Some cemeteries have websites where you can search for graves. Magnolia Cemetery in Augusta has a great search function and if you search for our name you will get several pages of results, including people I can’t connect to our family, plus a number of black people with our same last name buried at another cemetery. Almost all of the old Augusta people are buried at Magnolia, so most of the ones listed in the census show up in the cemetery with the dates they died (and sometimes birth dates), including some children who never lived long enough to be in a census. All three Irish brothers, John, Lawrence, and Patrick, show up in Magnolia’s records, though the only thing I have saying they are brothers is what Edward wrote.

While looking for records about our ancestors from New Orleans, I found mentions in the local newspaper, The Daily Picayune. But you have to pay to join newspapers.com to see the archived pages. You can get a week free, so I did that and was able to find a few articles that helped fill in some information. Also I found mention of some Augusta relatives mentioned in the catholic newspaper The Southern Cross, which is online. You can read the articles (including this page which has the obituary of my great grandfather), but you can’t save them because they have some javascript that prevents most people from right-clicking to save the scanned image. Magnolia Cemetery’s website said Patrick was an engineer and died in an accident along with someone else buried there. I looked up his name and accident and found an article in the New York Times saying he died in a train wreck on the Augusta and Savannah Railroad (which went to Millen, not Savannah) when a culvert washed out in August 1867.

These things aren’t entirely reliable. The census and newspapers are scanned and converted to text and Google is indexing the text, but scanning is never perfect and a lot is misspelled which means a search won’t pick it up. Census records in particular are usually hand-written, so if they are scanning those, they are doing pretty well. There are also projects where people type in what is in the census which is much more accurate, but a pretty big job. Some ancestry.com census records show you the text as you are viewing the document which makes it pretty easy. And some cemeteries don’t have electronic records at all, for instance Elmwood in Birmingham, which has tens of thousands of graves, still relies on looking stuff up on index cards. And while genealogists offer to transcribe the records, the cemetery doesn’t seem interested. In fact, supposedly they will run you off if you try to take pictures and enter info on findagrave.com, though Bear Bryant’s grave is there anyway. Ancestry.com runs reasonably fuzzy searches so if they hit on anything close to what you are searching for, they will let you know. Plus they have a pretty good idea of what is useful based on all the family trees and sources other people have found and cited. I looked and looked for records about my great, great, great grandmother, Louisa Stevens, and ancestry.com was able to point me to her grave in Mississippi. This was despite me looking for the spellings I found in the census which had her name as Eliza and the spelling of her last time varying between Stevens and Stephens.

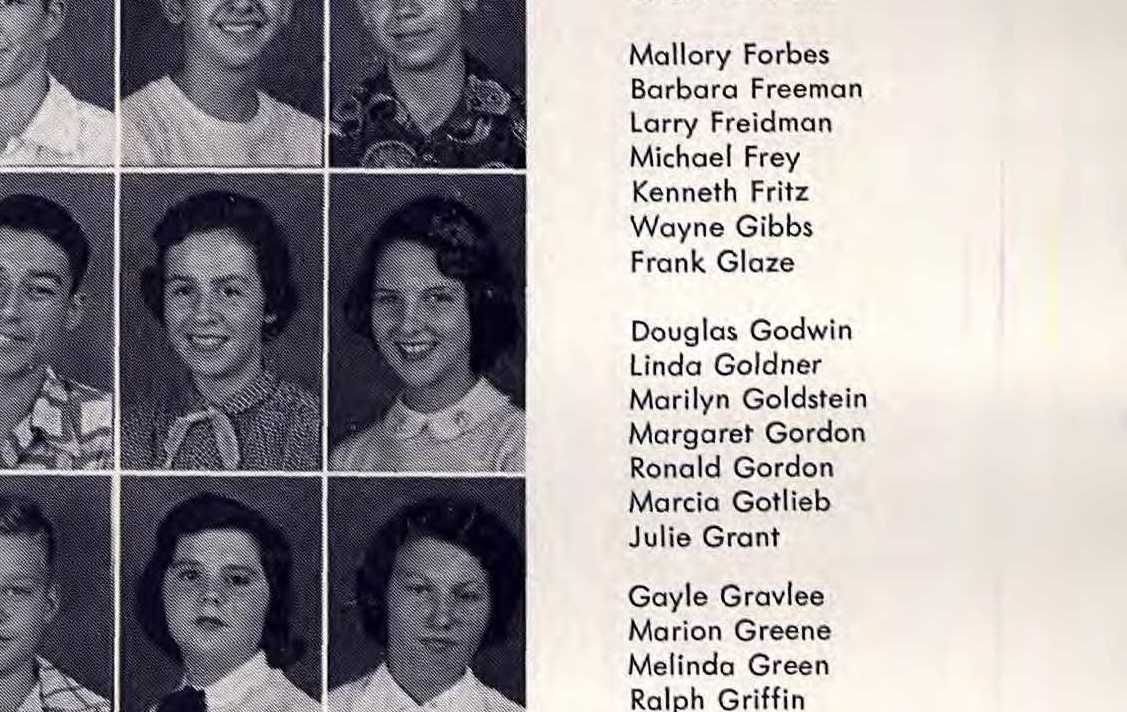

There are other things ancestry has that could be useful. One of them is scanned phone directories, so you can figure out where people live in a given year. Also they have scanned some school yearbooks, which is kind of fun if not all that useful.